As part of their series, “The Other Side of Anger”, NPR science reporter Michaeleen Doucleff retraces the steps of anthropologist Jean Briggs who lived with the Inuit in the Arctic Circle in the 1970s to learn “How Inuit Parents Teach Kids to Control Their Anger”. Traveling to Iqaluit, Canada, Doucleff attends a parenting class where the golden rule is “don’t shout or yell at small children.”

“Traditional Inuit parenting is incredibly nurturing and tender,” she reports. “If you took all the parenting styles around the world and ranked them by their gentleness, the Inuit approach would likely rank near the top.”

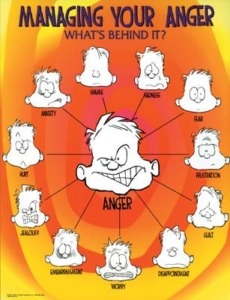

The secret, Doucleff is told, is to understand that children acting out are not trying to push adults’ buttons, but are upset about something. It’s up to the adult to figure out what that is. While this parenting style is centuries old in the Inuit community, it goes along with what modern psychologists believe: when you demonstrate anger to small children, you teach them to be angry.

“When we yell at a child — or even threaten with something like ‘I’m starting to get angry,’ we’re training the child to yell,” says clinical psychologist and author Laura Markham in Doucleff’s report. “We’re training them to yell when they get upset and that yelling solves problems.”

In my years of working with families, I have seen the impact of yelling at children first hand — they yell back. Every time a parent lashes out at a child, either verbally or physically, the child absorbs an important lesson about anger: if you’re angry, you get to yell, scream, and even hit.

Goota Jaw, who teaches parenting classes at the Arctic College, say that even timeouts teach the wrong lesson: “Shouting, ‘Think about what you just did. Go to your room!’ ” Jaw says. “I disagree with that. That’s not how we teach our children. Instead you are just teaching children to run away.”

Instead Jaw and the other parents she works with rely on story-telling to impart lessons to their children, using many of the same stories that were passed down through generations. Oral storytelling teaches children valuable lessons about respecting others, and making safer choices.

And again, modern psychology agrees with this lesson: “Don’t discount the playfulness of storytelling,” says psychologist Deena Weisberg at Villanova University, who studies how small children interpret fiction. “With stories, kids get to see stuff happen that doesn’t really happen in real life. Kids think that’s fun. Adults think it’s fun, too.”

While the lessons of Inuit parenting are sound, carrying them out is more challenging in part because most parents never learned these same lessons as children. When their own discipline was to be put on timeout, or yelled at or even smacked, it’s hard for them to have enough emotional regulation of their own to teach it to their children. They have to be able to control their own anger in order to teach their children how to control theirs.

This becomes more complex when you add in all the other stressors of modern parenting, including work, home maintence, and the ever watchful eye of other parents.

When Doucleff tries to use the lessons she learned from the Inuit in her own parenting, as outlined her in her follow up article “Can Inuit Moms Help Me Tame My 3-year-old’s Anger?”, she struggled to control her own anger in the face of her daughter’s tantrums: “I admit that following this advice was really hard,” she reports. “I mean really, really hard. It took weeks of practice. At first, I just stopped saying anything to Rosy when she had a tantrum or hit me. I knew that if I opened my mouth, the words would be tinged in anger. So I would just close my eyes to calm myself down and then wait for Rosy to calm down herself.”

At first she struggles to get used to using story telling instead of logic to get her daughter to do things, until one day a story about the monster living in the refrigerator (who gets bigger the longer the door is open) made her daughter close the door faster than any explanation about all the energy being wasted could: “Holy moly! You should have seen the look on Rosy’s face,” she reports. “She closed the door lightning fast, turned around and said, ‘Mama, tell me more about the monster in there’. Since that moment, storytelling has become a go-to parenting tool in our home. Rosy can’t get enough of these stories and even asks me to make them scarier.”

But possibly the most interesting bit from Doucleff’s series of reports about Inuit parenting is how they tap into the same ideas of Structural Family Therapy. Inuit parents act out interactions with their children, including the the children hitting them or yelling at them, and dramatize their reactions with an exaggerated “ouch!” and questions about if the child likes the adult. Then they act out the scene again the way they wanted the child to behave. While Doucleff called these “dramas”, SFT Founder Salvador Minuchin called these “enactments”, but both accomplish the same task — letting a child experience consequences of their behavior in a safe way, and then experience how that same interaction could go better.

Ultimately, the best way to help children with their anger is for parents to have a handle on their own. The more both parent and child have positive experiences of managing anger, the better both will be at it (and the easier it will be for parents to continue to manage their children’s tantrums). Ultimately the Inuit children grow up to become the adults able to manage the anger of the next generation, and gently guide them back toward emotional regulation.

Connection, again, is key. But the inherent struggle of connection is that it presupposes that you are worthy of it. Many of the individuals and families I encounter don’t feel worthy of connection. It’s part of what keeps them isolated (I strongly recommend you watch the above video in its entirety).

Connection, again, is key. But the inherent struggle of connection is that it presupposes that you are worthy of it. Many of the individuals and families I encounter don’t feel worthy of connection. It’s part of what keeps them isolated (I strongly recommend you watch the above video in its entirety).